Both the revision of rules for elk hunting trials and the implementation of Hirvenhaukut trials, an annual national elk hunting championship competition, were significant milestones for the development of the Karelian Bear Dog. The use of the breed for elk hunting and attendance in trials increased, even though registration numbers hit a low point in the mid 1960's. Individuals that showed exemplary working traits, such as Pete and Murri from Sweden, broke preconceptions about the breed being bad at elk work.

The executive committee for the Finnish Spitz Association, Suomen Pystykorvajärjestö, decided in 1958 to revise the rules for elk hunting trials to facilitate breeding of working dogs as well as to increase activity regarding trials, with the goal of obtaining much needed information for selective breeding. Ahto Virrankoski was appointed to take responsibility over this task and the work was completed in time for it to be approved by the annual general meeting in 1957. Rikhard Sotamaa made a proposal to the Finnish Kennel Club’s council on 13th April 1956 to implement a national Hirvenhaukut championship trial for Karelian Bear Dogs. The proposal was however tabled. Heikki Kirra kept promoting the cause in a form of a written proposal, that applied to all Nordic elkhound breeds, to the 1957 annual general meeting of the Finnish Spitz Association. The proposal was approved with reservations and the executive committee was assigned with further development.

Under leadership of Jaakko Simonlinna, the chair of the Finnish Spitz Association, Kirra’s proposal was revised to apply on the Karelian Bear Dog and development of a domestic elkhound. Antti Tanttu and Rikhard Sotamaa marked out the goals and execution of this competition to be strongly for breeding purposes. The Finnish Kennel Club’s council approved the rules for the Hirvenhaukut championship trial for Karelian Bear Dogs on 11th May 1957. The first championship trial was held later that same year, on 10th and 11th November in Huittinen. Panu (5031 A), owner Heikki Kirra, was crowned as the first Hirvikuningas. The title literally translates to Elk King.

The Karelian Bear Dog’s ability to bark at elk and its heritability – Tanttu’s data evidence

In order to create a base for development of elk barking traits, Professor Antti Tanttu researched in 1945–1958 all bear dogs awarded at elk hunting trials, their trial performances, and pedigrees. The aim of the research was to establish, based on this data, whether it is possible to make impartial conclusions about the ability to bark at elk and the heritability of this trait.

During 1945–1958, bear dogs had gained 119 results entitling for a prize in elk hunting trials. These dogs included 63 different individuals, of which 23 had gained several different prizes. 30 dogs had gained a demanding first prize. With this statistical analysis, Tanttu stated to have simply overturned the common idea that a bear dog cannot hunt elk. To establish the heritability of elk barking traits, Tanttu also drew up pedigrees for all 63 prize-winning dogs. In the summary of his study, Tanttu stated that only eight prize-winning dogs did not have the influence of Antti Herrala’s progenitor Jeppe present in their pedigrees. Of course, Jeppe did not have any results from trials, but the fact that Jeppe was sentenced to death by the court because of his good elk barking skills can be considered as strong evidence of this trait. The court found that it was endangering the “state’s cattle”.

In addition to progenitor Jeppe, other males that have had an influence on elk barking skills include Jeppe’s son, model dog Töpö, as well as Töpö’s sons Kiho-Tuisku, Kiho-Myrsky, Kiho-Hiisi, Herjan Teppo, and Herjan Nalle, or some of the sons of Töpö’s full brother Möttö. In most pedigrees, these dogs appear several times since strong inbreeding had to be done when breeding from a very small number of dogs. Viljo Kivikko’s Selki appeared in the pedigree of 44 awarded dogs, Tuusik in 36, the first double champion Kyttä in 24, and the completely black Mischa from southern Olonets in 14. Prokko (11104/X), son of Selki and Saida, was, despite his young age, in the pedigrees of more than 10 prize-winning dogs, including Santtu (4386/56 J, owner A. Ahola).

Due to the irregular distribution of data, Tanttu found that he could not reach the goal of his study, in other words make any impartial conclusions about the heritability of elk barking skills. He did however state the following:

“We have been able to maintain the will and ability to bark at elk, passed down from ancient times, in Karelian Bear Dogs. The newcomers of the 1940’s have been mated to the old population. These matings have fit the purpose and resulted in hunting traits to commonly appear in the progeny.”

From the results, it could be seen that six of Selki’s, four of Kyttä’s, three of Prokko’s, and two of Tuusik’s first-generation offspring had already been included in the list of prize-winning dogs.

Pete – a dog that could work all day long

At Hirvenhaukut championships held in Oulu, Vallinkorva forestry school in 1959, the two-year-old, tricolour male Pete (1190/57) turned up to the trials. Its handler was a hunter of large game, Heimo Rautava from Ilomantsi. At its first try, Pete barked its way to victory and gained the title of Hirvikuningas. Pete cleared its path to the championship trials altogether five times. It barked a first-prize result altogether 13 times and countered allegations about Karelian Bear Dogs not being able to bark all day long.

At the Vallinkorva trials in 1959, where Pete achieved the title of Hirvikuningas, the day was however cut short upon judge’s decision. Pete was seeking for one hour and 5 minutes, until it found elk at 9.25. At first, the bark was partly steady, partly moving. Helge Saarikoski, chief judge of the trial, came within sight from the elk at 9.59 together with the dog’s owner, and saw Pete luring the elk towards the group. It advanced backwards leading the elk and barked calmly at the elk’s muzzle. The pair came as close as 40 metres from the group and Pete held the elk at bay with a steady bark. Visuri, who served as a guide at the trial, asked for permission to make a shot. However, the chief judge found that a shot would be relevant only after the dog had held the elk at bay for two hours. At 11.30, he gave permission, and a shot was fired but missed the elk. The elk ran away in full speed and Pete ran after it. The group tracked the pair for six kilometres without noticing any blood tracks on the way. Pete reported to the group at 13.15 and was put on lead upon judge’s decision, and the trial was ended.

Pete was an excellent hunting dog, and, thanks to its pushy temperament, it also barked at bear. It passed down its working traits well to its offspring. This can be proven by the fact that by 1968, four of Pete’s sons from different regional districts had participated in the Hirvenhaukut championships. Usvan Sissi (3146/61, owner Veikko Mielonen) from the eastern district became a two-time winner of Hirvenhaukut championships. Other Pete’s offspring to have participated include Töpö Syti from the eastern district, Usvan Peku from the southern district, and Prikku from the western district.

Murri from Sweden – the most expensive dog in the Finnish Karelian Bear Dog history

Heikki Jeronen from Karijoki had a bobtailed male name Murri (2617/55 H, sire Jeppe) that showed promise already at a young age. It made its first two kills at the age of seven months. The man’s trust in his dog is well described by the fact that when Jeronen took Murri to its first trials in Laihia, he announced that Murri would take results in both open and winner class on the same day. This would also have been the case if the rules only had allowed it. To its appearance, the dog was of certificate quality and able to become a double champion. Therefore, men of means were very interested in the dog.

Murri had already 33 kills in its records when it was sold to Sweden at the age of three years. It went to J. Blom‘s kennel av Jobs, mentioned to be the largest Karelian Bear Dog kennel in the world, having sold 1026 Karelian Bear Dog puppies by the beginning of 1959. The dog had been found to be a gifted one as regards to keeping elk at bay. Lauri Vuolasvirta, who served as a breeding advisor, did everything in his power to find a Finnish buyer for Murri to not lose a valuable, top-class male to Dalarna in Sweden. However, for the price Blom paid for the dog, a Finnish farmer was able to buy a much-needed tractor including farming implements. Murri ended up as a breeding sire at kennel av Jobs. When Vuolasvirta visited Murri in Dalarna in 1959, the well-ran kennel had 30 Karelian Bear Dog females that were not used for hunting. When visiting, six females had litters sired by Murri. Even though Murri became a double champion also in Sweden, its breeding merits remained weak in Sweden, as the emphasis there was in producing handsome country house dogs. Losing Murri weighed on the minds of Finnish bear dog enthusiasts, resulting in Eero Peiponen (kennel Peiron) repurchasing Murri in 1960 by trading it for the stunningly beautiful double champion Jepen Jeri, who had also competed in the Hirvenhaukut championships in 1958. After that, Murri was used extensively for breeding in Finland, and it was still a good hunting dog even in old age.

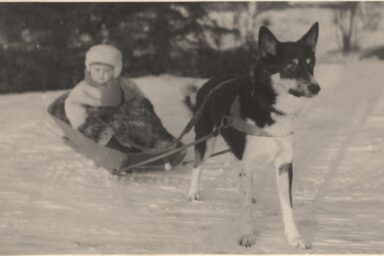

In a main picture on the left Selki, on the right Saida and between them their puppy Ontro.

The text is a passage from historical texts written by Eila Lautanen, published in the 80th Anniversary History of the Finnish Spitz Association, Suomen Pystykorvajärjestö – Finska Spetsklubben ry. It was published in 2018.

Photographs are from the collections of the Finnish Kennel Foundation and the Hunting Museum of Finland.