Artist Jussi Mäntynen drew up a seal that would be used to confirm the documents of Kennelklubi, the precursor of the Finnish Kennel Club. The seal illustrated a Finnish Spitz which was back then known as the Finnish Barking Bird Dog. The dog in the picture was surrounded by the text Finska Kennelklubben – Suomen Kennelklubi. The Finnish Kennel Club used the same symbol, until it was modernised for the World Dog Show in 1998. The new symbol for the Kennel Club was released in the beginning of 1999. It illustrates the silhouette of the head of Finland’s National Dog, the Finnish Spitz, in a stylised way. The symbol was designed by Pekka Lehtinen, the art director for a large Finnish publisher of magazines Yhtyneet Kuvalehdet. The old, round symbol for the Kennel Club continued to be used in flags, honorary decorations, and medals.

I was once again on a hunting trip with my dog Pinni, in the Koiravaara terrain in Sotkamo, Northern Finland. I had left my vehicle to the other end of a forest trail, where the road formed a loop. We had already travelled for several hours towards south. Pinni had shortly barked up at black grouses a few times, but the birds had been very shy and had not stayed in the tree. The gun I was carrying on my back started to feel a bit heavy and I was getting tired of walking. I had already turned around and started to walk back, towards the car. I noticed from the tracker that the road was quite close, and decided to walk the remaining distance to the car on the road instead of the forest. There was still just over a kilometre left to walk.

I walked the road for a while. Then I heard distant barking next to the forested hill behind me. I looked at the tracker and noticed that the sound was coming from Pinni. There was a 750 metre walk back to the dog. I moved a little closer – the barking was clearer than before and had become more continuous and frequent. I started pondering whether the dog was barking at a bird or some other animal. Then I remembered my son-in-law telling me about a litter of capercailzies he had ran into in the same area, and the decision was clear – the dog must be barking at a capercailzie, at least a female one. A thought about the animal being a squirrel flew across my mind, but I felt that the possibility of the target being something other than a bird was very small.

I started walking towards the dog with new vigour. Her barking was still continuous and rapid. It took me more than half an hour to approach, and of course I had to move more carefully the closer I got, otherwise the capercailzie would flee. I approached the spot very carefully, and finally, in the top of a pine tree between two sturdy spruces was the oblong target with a furry tail – a SQUIRREL. I commanded the dog away, pointed the direction for her and started walking.

Pinni was not very eager to stop barking, but finally obeyed. We left the target to the forest and went back towards the car. Not once did it cross my mind that I had made the wrong call by checking which target the dog had barked at – it could have also been the desired one. Barking at squirrels is, unfortunately, written very strongly in the genes of the Finnish Spitz, and is not easily erased.

The trip to the forest was done for the day, and we drove to a hunting cottage to cook sausages over an open fire. We may not have caught anything that day, but at least I got to spend the day outdoors with the greatest dog in the world.

In Kajaani 15.3.2016

In the main picture: Pinni, first dog from the left. Picture: Hannu Huttu

The operations subsided in the Continuation War in Finland 1944–1944 when the front lines stabilized. The amount of wounded people reduced and I started visiting the near forest with my shotgun. Already during the second or third time I noticed I was not walking alone. I was followed by another hunter; a dog looking a lot like a Finnish Spitz flashed now and then between the trees and kept me company the whole way. He was approximately four or five years old and scared, mistrustful, and afraid of humans. It turned out he had no master, no name, and no home. When the Winter War in Finland 1939–1940 had ended, the dog had stayed in his home region and somehow managed to stay alive – nevertheless, he was in good condition. Someone had seen a flash of him before, but mostly the dog was hiding. He did not have any friends, and no one knew where he got his food from.

Little by little, the dog became less shy, but he never came close enough for me to pet him. We shared my lunch sandwiches, which he happily ate, but he never took anything directly from my hand. He did, however, lie down closer and closer to me whenever I stopped for a cigarette. His trust for people was clearly coming back. A man going to the forest with a shotgun was something that helped him get over his fears, he could not resist it, the dog had hunter’s blood running through his veins. He was a dog able to hunt all game. He barked at birds and squirrels and went even after a rabbit a few times, just like the spitz of old-time hunters used to do. He appeared every time when I went to the forest, and disappeared every time I went back home and got closer to the village. He was keeping an eye on me from some place hidden.

Before Christmas I was able to shoot a capercailzie with the dog’s help, and sent the bird to my parents living in Helsinki. I had planned to try and bring the dog home with me somehow. We had become friends. Then, a warning for a rabies epidemic was declared to the Karelian Isthmus, and an unconditional demand was set: every dog with no master must be shot!

I was told to put down this particular dog. There was no room for negotiations, an order was an order and it had to be followed immediately. So I took my shotgun and went to the forest, and the dog, as usual, followed me. There was no leash. Suddenly, he scampered off, like he knew something bad was about to happen. I had to shoot at him from a 70–80 meters distance, and he fell down, but did not die immediately. I ran to the dog lying on the ground to give him the finishing move. He turned his head with difficulty, looked me straight in the eyes with a submissive look, and said: Even you, my only friend.

The Finnish Spitz in the main picture is not involved in this story.

An old poodle painting from the 19th century was restored because of the damage on the paint surface. The painting was also cleaned in the same process.

Workflow

- Removing the painting from its frame

- Cleaning

- Repairing the damage on the surface

- Applying paint on paint losses

- Reframing the painting

First the painting was removed from its frame, so that the frame and the back of the painting could be cleaned from dust. The paint surface was cleaned with triammonium citrate and finally with water.

Sturgeon glue was used as an adhesive on the cracks and the small paint losses. Sturgeon glue is colorless glue commonly used in restoration, and it is made of the swim bladder of the sturgeon fish. While applying the glue, the cracks with lifting edges were pushed down with heat and weights.

There was an old hole on the right side of the painting, which had been patched up poorly during the earlier conservation. The old caulking was removed mechanically. The damaged canvas was patched up by organizing the fibers and gluing them together with a mixture of sturgeon glue and wheat starch. A piece of polyester voile with glue coating was put on the backside of the canvas for support.

After this, the paint losses were filled with putty, and restored with restoration paint.

Finally, the rabbets of the frame were padded to stop the edges of the painting from rubbing against the wood. Metal strips were added to the frames for hanging the painting. Hangers were also added to the frame, in addition to the already existing tab on the upper side of the frame. The hangers make it possible to hang the painting on a picture rail, when needed.

Restoration report and pictures by Anna Lehikoinen, Konservointikilta

Suomen Kennelklubi, the precursor of the Finnish Kennel Club, was established May 11th 1889. The date can be considered as the starting point of organised kennel activities in Finland. The Finnish Senate confirmed the by-laws of the Club, and artist Jussi Mäntynen drew up a seal that would be used to confirm the Club’s documents. The seal illustrates a barking bird dog – the Finnish Spitz.

Once the Kennel Club expanded, specific sections were needed for carrying out different tasks. The Spitz got their own section as well when the Spitz Section, Pystykorvaosasto, was established in 1902. It took primarily care of matters related to the Finnish Barking Bird Dog, but in 1916 the Karelian Bear Dog was also mentioned in the documents.

The Spitz Section held together until 1921. Due to conflicts, a separate club for the Spitz, Pystykorvaklubi, was established December 31st 1922. However, the club disbanded already in 1925. Then again, the Spitz Section continued its activities through the following decade.

Due to disagreements on the language policy and the possibilities to influence, Suomen Kennelklubi split up in two. The founding meeting of Suomen Kennelliitto was held March 16th 1935. This lead to the establishment of nationwide breed associations. The founding meeting of the Finnish Spitz Club, Suomen Pystykorvajärjestö, was held at Helsingin Seurahuone May 6th 1938.

The dichotomy continued until 1962 when Suomen Kennelklubi and Suomen Kennelliitto merged into a single organisation, the Finnish Kennel Club, officially named as Suomen Kennelliitto – Finska Kennelklubben. The combining of the clubs led little by little to the merger of sections and breed associations. The Spitz were reunited in 1964 as the Spitz Section and the Finnish Spitz Club merged into one association, the Finnish Spitz Club, officially named as Suomen Pystykorvajärjestö – Finska Spetsklubben.

The by-laws for the new association were approved in the founding meeting of the Finnish Spitz Club. The Finnish Spitz was defined as the only subject of interest. In the annual general meeting in 1950 the by-laws were revised to include the other Finnish domestic Spitz as well.

A delegation elected by the general meeting oversaw the activities of the association. The delegation elected a chair among its members, as well as a separate board to take care of different matters in the association. Gradually, the board became the primary body to carry out the tasks. The delegation was entirely given up in the revised by-laws in 1950.

The mission that was set for the Finnish Spitz Club was to cherish and preserve the breed that was bred directly from the native landrace dog population.

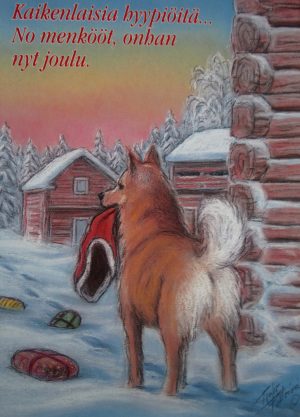

Finland’s national dog, the Finnish Spitz, is an established part of the Finnish folklore. For decades, the red coated dog has followed its master in illustrations and stories in books, post cards, as well as in the cinemas. Artists and sculptors have also been inspired to illustrate the Finnish Spitz as one of the symbols of Finnishness.

A dog barking under a spruce is portrayed even at the 19th century Finnish folk poetry. One part of the Kanteletar poem collection collected by Elias Lönnrot describes as follows (translated from Finnish to English by Angela Cavill):

Now make my dog call,

make my searcher bark,

inside the blue wilderness,

in the golden dome of the wilderness,

do not make him bark pine twigs,

do not make him call spruce branches,

but make him bark at something under fir twigs,

something sitting on a spruce twig!

The importance of the Finnish Spitz as a part of Finland’s culture can also be seen in several illustrations. Many Finns remember the Spitz from the traditional ABC book, as well as from the illustrations in Finland’s national epic Kalevala and the novel Seven Brothers, which is written by Finland’s national author Aleksis Kivi. Many post cards illustrate the Finnish Spitz as a part of its family’s daily life as well.

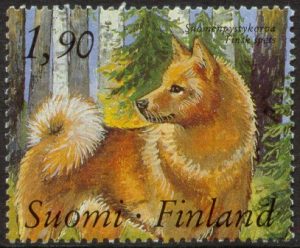

To celebrate the Finnish Kennel Club’s 100th anniversary, a stamp sheet was published in 1989. The sheet contained four different stamps, each one illustrating a Finnish dog breed, one of which was the Finnish Spitz.

The Finnish Spitz has even had the lead role in several Finnish works of art. The significance of the Finnish Spitz as a literary figure

is brought up for instance in the novels Musti written by Eino Leino, Peni written by Heikki Lounaja and Koirankynnen leikkaaja written by Veikko Huovinen. Markku Pölönen directed a movie based on Koirankynnen leikkaaja, Dog Nail Clipper, where the lead role, the Finnish Spitz Sakke, is played by Korpisaran Tuuli. Even Veikko Huovinen was so impressed by Tuuli’s performance, that he sent the dog a fan letter.

The Finnish Spitz in paintings and sculptures

Several artists portraying the Finnish nature have immortalised the Finnish Spitz in its natural environment, in other words in the Finnish forest. It tells something about the strong influence of the Finnish Spitz that it has been portrayed by Finnish artists for decades, all the way from 19th century artist Akseli Gallen-Kallela to 1960’s naïve artist Viljo “Jalo-Valmari” Mäkinen.

Noteworthy sculptures illustrating the Finnish Spitz are Peni (1989) by Pekka Ketonen and Sokerityttö (1956) by Viljo Savikurki. The latter portrays a girl and a dog, and is displayed at Mannerheimintie in central Helsinki. Back in the day, the headquarters of a sugar factory, Suomen Sokeri Oy, was located at the very spot – Sokerityttö stands for Sugar girl. The Finnish Kennel Club holds a statuette that might have been Savikurki’s sketch for the real sized statue.

Main image © Terho Peltoniemi

The Finnish Spitz barks at birds up in trees and is therefore an original rarity in the world. It is a dog with veiled intelligence, and it has a strong instinct to hunt all types of game. It is quick on the mark and capable of doing independent and confident decisions. It indicates the location of the bird with its barking and behaviour, and will try to keep the bird in the tree by barking until the hunter gets there. When the Spitz barks at the tree its handsome wobbly tail “enchants” the bird.

The Finnish Spitz significantly helped its master to provide livelihood. The woods and the waters were almost exclusively the only places that provided food. In the woods for instance, using its clear bark the dog informed its master about the location of the bird. Wobbling its light-coloured tail, the dog charmed the bird to remain in tree so that the master had enough time to find the tree and shoot the bird with his bow.

Today the Finnish Spitz has learned to understand and apply its instinct to hunt. We have come to an age when the dog is instructed with the rules and regulations that are related to its master’s competitiveness.

In other words, the Finnish Spitz is able to focus on the same game as its master sets his mind on. It is a dog that retains a great connection with its master in the forest. Life has thought the Finnish Spitz that the greatest threat in the woods is a wolf. While the Finnish Spitz is intensively focusing on its job to bark a wolf can easily find and surprise it. The dog takes care of its safety by keeping the distance to its master at a few hundred metres at the most.

The Finnish Spitz was once inexpensive to support. It used to find its food itself, which probably explains why the dog eats very little today as well. It is still fascinated by mice and moles, since these creatures used to be its primary nutrition back in the day.

It was mainly the Spitz that used to be in charge of getting money – with other words, fur. The currency unit at the time was called “kiihtelys” which included 40 squirrel skins. Who else would find fur game and reveal its location to the master if not “pikinokka”, the Finnish Spitz with its pitch black nose. The Spitz was brave and independent enough to confront and hunt the bear: many skins were hanged to dry, thanks to the dog’s barking. There are also several stories about times when the dog has saved its master from a bear by nipping the bear from behind, and by doing so giving its master time to escape. The Finnish Spitz developed almost a passionate relationship with hunting squirrel and pine marten. This feature is clear in some dogs even today.

Today the Finnish Spitz is used mostly for hunting grouse birds, although it can be used when hunting elk and small game, such as pine marten and raccoon dogs, as well. It has always been considered as a dog that is capable of hunting any kind of game, and is therefore very easily trained to do so. The Finnish Spitz is also used as a retrieving dog for instance in duck hunting. Its most important feature is its loyalty towards its master, both at home and in the woods.

The national dog of Finland, the Finnish Spitz, is by far the oldest of all the Finnish breeds. It was bred directly from the native landrace dog population without crossbreeding, and it has followed the Finnish people since ancient times. A dog similar to the Finnish Spitz has been found in prehistoric cave paintings. The Finnish people lived in isolated residential areas in the wilderness in the Northern part of Finland, from Kainuu all the way to Murmansk, and their dogs remained purer in comparison with dogs living more south where they easily got mixed with other dogs.

The Finnish Kennel Club, Suomen Kennelklubi, was established in 1889. “The Emperor of Lapland”, master forester Hugo Richard Sandberg was involved in the Kennel Club at the beginning. He wrote an expert description of the Finnish Barking Bird Dog in the Sporten magazine published December 12th 1980. In the paper Sandberg presented a suggestion for the dog’s breed characteristics. He was encouraged to write the paper by Alex. Hintze, a journalist in the Sporten magazine, who was involved in the establishment of the Finnish Kennel Club. Hintze was the chair of the Finnish Kennel Club from 1889 to 1892.

The paper written by Sandberg laid the foundation for the work of the Kennel Club. The Kennel Club confirmed the characteristics Sandberg had suggested, and the Finnish Barking Bird Dog was added to the pedigree book. Hereby was the birth of the Finnish Spitz, Finland’s national dog, confirmed: a new breed standard was confirmed in 1897 and the name of the breed was changed from the Finnish Barking Bird Dog, “suomalainen haukkuva lintukoira”, to Finnish Spitz, “suomalainen pystykorva”. In Finnish the name reached its final form, “suomenpystykorva”, in 1946.

The Finnish Barking Bird Dog, as the breed was originally known as, was tall to its body and had a fox-like coat. It could have plenty of white colouring in its chest, legs and on the tip of its tail. In the next breed standard from 1897 the name of the breed was changed to Finnish Spitz, “suomalainen pystykorva”, and the length of its body was defined as stumpy. The breed standard has been revised six times, and the latest version was confirmed in 1996.

The first show for Finnish Spitz was held in Oulu in 1892. So far, the majority of the rewarded dogs were from the vicinity of Oulu. 93 Spitz were presented for judging. A read coated male Kekki was the winner of the show, and received 30 Finnish Markkas for his victory. Kekki is entered into the Finnish Kennel Club’s first pedigree book 1889–1893, and is marked with the number 1.

Breeders fancied square-like males in the beginning of the 20th century. Dogs who influenced the most in the beginning were the male dogs Halli af Tampio and the first Champion dog Nätti, owner Antti Tanttu. One of the pioneers for breeding of Finnish Spitz was forester Hugo Roos. Roos started to breed Spitz very determined, and had great possibilities for trying out the hunting qualities of the dogs in Lapland and Kainuu in Northern Finland. The breed characteristics for the Finnish Spitz were revised in 1897 with Halli af Tampio as a model.

The Finnish Spitz is smaller than the average, has a square, solid structure and good posture. Its ears are erect and mobile. The eyes are mid-sized, almond shaped, slightly slanted and dark. The nose is always black. Its starting speed is explosive when necessary and it moves with effortless lightness. Its entire appearance and expression is one of vibrant attentiveness. The Finnish Spitz is yellowish or red-brown in colour. The colour is usually bright. It is adorned with lighter hair on the back thighs and sometimes in the shape of reins on the sides, in addition to which the inner arch of the tail is light.

The Finnish Spitz was declared Finland’s national dog breed at the Finnish Kennel Club’s 90th anniversary show. Dressed in an old hunting outfit, the then chair of the Finnish Spitz Club, Erkki Uutela, presented a Finnish Spitz for the audience.

Recently the Finnish Kennel Club has actively worked for including the hunting experience with the Finnish Spitz on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List.

The nomination traces back to the preparations of Finnish Kennel Club’s 90th anniversary when Jouko Yrjölä, a member of the board of the Finnish Kennel Club, suggested that the Finnish Spitz could be declared as Finland’s national dog. Heikki Sarparanta, the vice-chair of the Board of the Kennel Club, as well as the vice-chair of the Board of the Finnish Spitz Club got very excited about the idea and took care of the practicalities.